The last year has been a dumpster fire for the norms of international relations. Many of the foundations of the modern international order have been brought into question, from the UN to the WTO to free trade in general. Although occasionally good results have come of this, for the most part it’s been extremely bad news, dominated by two terms in particular: Trump and Brexit.

An endless supply of analysis has been thrown around, but one particularly informative sequence of events happened in response to Donald Trump’s unilateral declaration of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in late 2017. Immediately thereafter, a UN Security Council vote was called to affirm the invalidity of Trump’s declaration, which the US promptly vetoed.

Subsequently, the crackpot US Jerusalem policy was taken apart in the UN General Assembly in December 2017 with a humiliating 128 to 9 vote. Not that it changed much, since the US moved its embassy to West Jerusalem in May, deepening the longstanding conflict by resetting all talk of a peaceful solution to zero.

If there’s any lesson to be drawn from this kerfuffle, it is that the UN itself is an absolutely necessary body for guaranteeing international law, but that it is simultaneously a body hobbled by a structure that implicitly assumes that the global superpowers are generally worthy of the veto power they wield. In practice, nobody takes the UN seriously, and therefore there is no real backbone to international law.

The problem, of course, is that the UN General Assembly is a one-country-one-vote affair, giving China the same number of votes as Vanuatu, and putting the United States on par with Liechtenstein. The larger countries therefore have every reason to want veto power, the diplomatic nuclear option. But their veto is a little bit too much firepower most of the time, and it is frequently abused as a form of geopolitical bullying.

There is an alternative. The establishment of a UN Parliamentary Assembly, which would be democratically elected by the general public in each UN member state, with seats allocated in a reasonable proportion to the population of each country and based on rules guaranteeing representativeness within each country’s delegation, would give larger countries like China, India, the US and Indonesia a size-appropriate level of power in the affairs of the UN, with the current General Assembly being made into something like a senate. This model would bring a balance to the forces at work within the UN, and hopefully eliminate the need for Security Council vetos; leaving the Security Council itself better off for it.

While there are other possible approaches, this is one that resolves many of the valid criticisms of the UN as it stands, be it the unrepresentativeness, the lack of proportionality in the weighting of each nation, the substantial overkill involved in the current power structure of the security council, and the tendency of numerous smaller countries to be able to band together against the larger ones. It also furthers the goal of increasing public awareness of the work of the UN, which currently is residual at best.

This is not a new proposal. A Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly has been going on for many years, and has been endorsed by myself and more than 1500 other elected representatives in 122 countries. It’s not even a particularly radical notion. It’s simply a proposal to reduce the nuclear nations' reliance on the veto while giving the general public a much needed voice in the affairs of the UN. A soft power mechanism for global politics. Imagine!

But so far there hasn’t been a great deal of support for this kind of proposal. This is partially because the UN is an organization largely left to fend for itself. After Trump’s embarrassing defeat in the General Assembly, he further embarrassed himself and his office by petulantly defunding the UN to the tune of 258 million dollars a year. This nearly 5% budget cut for the international organization is a blow to global efforts to deal with humanitarian crises, international development challenges, and more generally the 17 Sustainable Development Goals which focus the global agenda. Trump’s most recent decision to defund the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) deepens the problem even further.

Some increase of enthusiasm is showing though. The European Parliament resolved in July to encourage the EU governments to support "the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly”, and more generally support a "UN 2020 summit" that will consider "comprehensive reform measures for a renewal and strengthening of the United Nations." This should absolutely be done, and I will be calling on the Icelandic parliament to pass a similar resolution in September.

Because, let’s face it: The UN is hardly anybody’s favourite organization and it has relatively few champions outside of its own ranks. Even core people understand the problems. The bureaucracy, the distance from the public, and the widespread (but entirely wrong) sense that it doesn’t accomplish anything do little to earn it public or political support. The political class in most countries treat it with something between disinterested reverence and confused fascination, and as a result it has become a refuge primarily for die-hard internationalists, romantic humanitarians, and ambitious careerists ─ all of whom are fighting the good fight, regardless of their reasons.

But the UN should be a favourite organization of a great many more people. The idea it was founded on, of upholding universal human rights and providing a platform for the world’s people to peacefully resolve their differences and move humanity towards a better future, is as lofty as any idea can be. And if Donald Trump’s misguided approach to diplomacy can be a rallying cry for greater support for that idea and the organization that upholds it, then make it so.

Either way, the UN needs to evolve. Its importance is clear, but it needs to become more human, less bureaucratic, more effective and less distant. The same is true of a great many international organizations, from the Council of Europe to the World Trade Organization. That Trump and others in the new wave of populist nationalism can so easily snipe at these organizations shows that they’ve done a poor job of engaging with the public and remaining relevant. They’re barely representative and largely misunderstood. To anybody who understands what these organizations are supposed to do, their importance is clear, but reform and modernization is long overdue.

This type of reform can be achieved, and now is the time to achieve it, before some petty despot does some real damage.

Smári McCarthy is a member of the Icelandic parliament, where he works on foreign affairs, international trade, and economic policy.

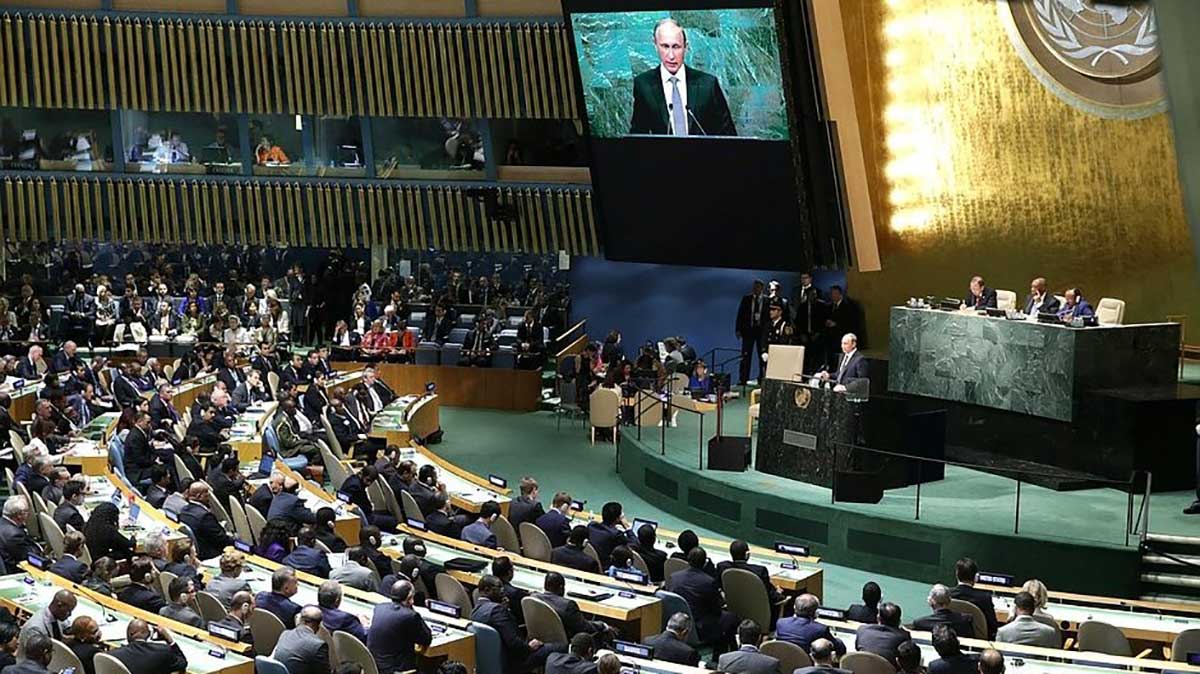

Image: Kremlin.ru