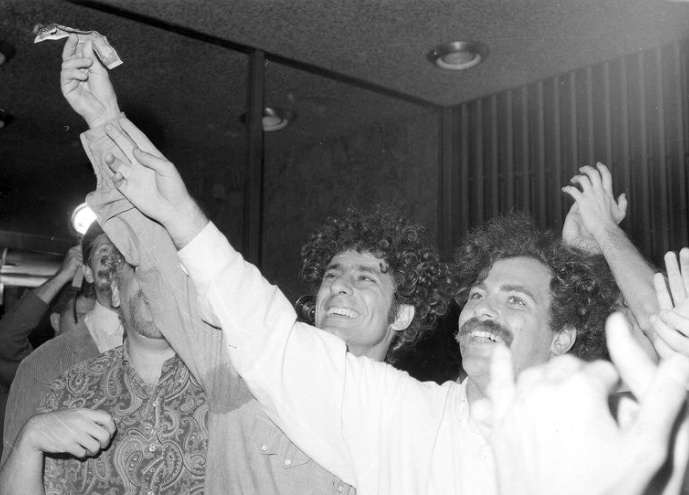

Participant Bruce Dancis recalled, “At first people on the floor were stunned. They didn’t know what was happening. They looked up and when they saw money was being thrown they started to cheer, and there was a big scramble for the dollars.”

The protesters exited the Stock Exchange and were immediately beset by reporters, who wanted to know who they were and what they’d done. Hoffman supplied nonsense answers, calling himself Cardinal Spellman and claiming his group didn’t exist. He then burned a five-dollar bill, solidifying the point of the message. As Bruce Eric France writes, “Abbie believed it was more important to burn money [than] draft cards… To burn a draft card meant one refused to participate in the war. To burn money meant one refused to participate in society.”

For Hoffman himself, the success of the stunt was obvious. “Guerrilla theater is probably the oldest form of political commentary,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Showering money on the Wall Street brokers was the TV-age version of driving the money changers from the temple… Was it a real threat to the Empire? Two weeks after our band of mind-terrorists raided the stock exchange, 20,000 dollars was spent to enclose the gallery with bullet-proof glass.”

"How the New York Stock Exchange Gave Abbie Hoffman His Start in Guerrilla Theater" (Smithsonian)